“No one can so use the navigable waters in front of the riparian owner’s property as to interfere with his rights, and when the owner wants to make improvements he can do so, even if they absolutely destroy any structure or other thing in the way of the improvements not there by the consent of the owner of the shore.”

This was the holding of Hodson v. Nelson, a decision of the Court of Appeals of Maryland in January 1914, almost exactly 100 years ago as I write. In the case, Mr. Hodson was a riparian owner of land surrounding a cove in the Chesapeake Bay. Mr. Nelson was a waterman operating a crab business in the cove, including erecting a “crab shanty” on piles not connected to the shore. The riparian owner sought to prevent the waterman from maintaining structures in the cove, but was not directly impacted by the crab shanty, and did not have a pier in the cove. Despite the strong language quoted above, the Court held that the landowner did not have the right to force the removal of the crab shanty.

In 1942, however, the Court of Appeals considered Culley v. Hollis, in which I riparian owner was built a pier that extended into an underwater oyster lease area. The waterman filed suit to stop the pier, but the Court of Appeals confirmed the fact that the riparian owner was allowed to build a pier, and that an oyster lease on the bottoms could not prevent the construction.

With the tremendous loss of oysters and crabs in the Chesapeake over the past 100 years, the tension between riparian owners and watermen diminished greatly, and has not been the topic of an important decision in decades. According to studies, the oyster population in the Chesapeake dropped to about 1% of historic levels by 1994, and has remained very low. In 2009, Maryland began a significant initiative to increase oyster populations — this effort included the streamlining and expansion of oyster aquaculture in Maryland. It should be no surprise that the expansion of oyster aquaculture has also created new tensions with riparian owners.

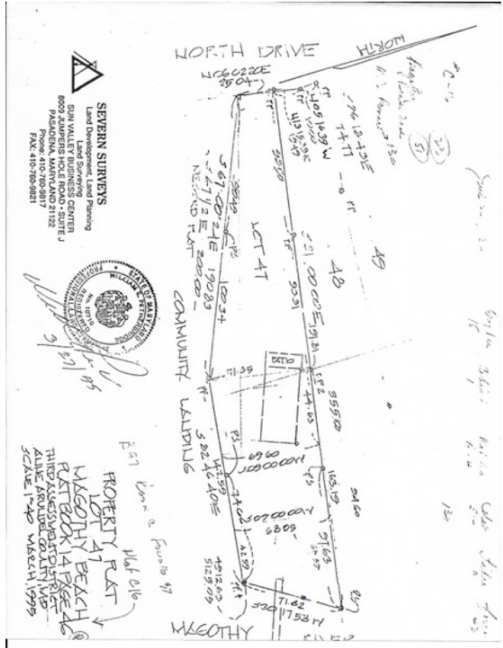

In recent months, I have represented two groups of landowners who were concerned about oyster leases being granted in front of their properties. In one instance, the primary concern was oyster floats anchored just off their property. The second involved oyster cages being placed in shallow water immediately in front of the groups’ properties and piers.

There are two types of oyster leases in Maryland. There are “submerged land leases” which allow a waterman to put shell on the bottom and exclusively harvest the oysters. There are also “water column leases” which allow the waterman to place floating baskets on the surface or cages on the bottom and grow oysters in that manner. There are a variety of restrictions and limitations on where a lease can be located, including leases may not be within 50 feet of a shoreline or pier without permission; leases cannot be in a submerged aquatic vegetation protection zone; and they cannot be in a public oyster fishery (typically a natural bar). My groups’ primary concern in both cases were with the water column leases, which placed equipment at or near the surface.

If you are faced with a lease being placed in front of your waterfront property, there are steps that you can take. If the proposed lease meets the statutory requirements, the DNR is required to provide notice to owners of property that will be directly affected. Riparian owners can file a petition with the Department of Natural Resources challenging the issuance of the lease. In all likelihood, there will be efforts to reach a compromise, but if not, a hearing will be held before the Office of Administrative Hearings. In that hearing, the DNR will present the case for the lease; the owners must be prepared to present concerns and arguments against it.

J. Dirk Schwenk is a Maryland Real Estate, Waterfront Property, Civil Litigation and Maritime Lawyer from Annapolis, Maryland. He provides civil litigation services in contract disputes, environmental and zoning issues, adverse possession and boundary disputes. He graduated cum laude (with honors) from the University of Maryland School of Law and has been in private practice in Maryland ever since.