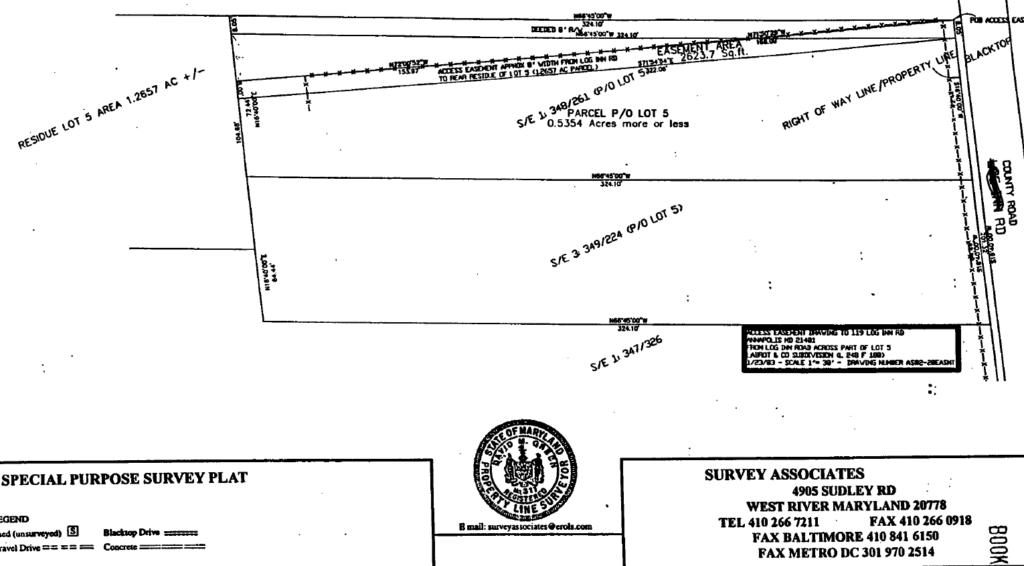

What kind of lawyer do you need if you have a dispute with a neighbor about easements, shared driveways or rights of way? Short answer: a good easement lawyer will have expertise in real property and who does civil litigation. In Maryland, all disputes about rights of way, boundaries, adverse possession and prescriptive easements are decided in the Circuit Court for the County in which the real estate is located. There are many real estate lawyers that primarily do closings and settlements. If you have dispute, however, you will need a lawyer that has a regular practice in the Circuit Court, so they are familiar with the rules of procedure; know the relevant experts and surveyors; and are familiar with the area in which the real property is located.

There are many marinas in Maryland, ranging from large commercial ones the size of small towns to “informal” (or illegal) ones with a few slips and a ramp. The purchase or sale of a marina property has all of the financial elements of a regular commercial property, but with highly specialized business, riparian rights, zoning, and environmental concerns. There are many risks to purchasers, and they pose very interesting questions for the real estate lawyer that knows about waterfront and marine businesses.

There are many marinas in Maryland, ranging from large commercial ones the size of small towns to “informal” (or illegal) ones with a few slips and a ramp. The purchase or sale of a marina property has all of the financial elements of a regular commercial property, but with highly specialized business, riparian rights, zoning, and environmental concerns. There are many risks to purchasers, and they pose very interesting questions for the real estate lawyer that knows about waterfront and marine businesses.